Logic Models and Learning: Four Fundamental Connections for Funders

By Philip Silva

Grantmakers want to see real-world results from the education initiatives they fund at non-profit organizations, but their grants rarely include the resources needed to monitor and measure longer-term impacts. That’s where the Learning-Transfer-Impact (LTI) model in Dialogue Education comes in. It offers grantees a cost-effective, evidence-based framework for demonstrating results.

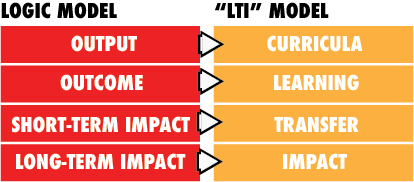

The LTI model has three simple stages: learning, where participants actively engage with new concepts or skills during an event; transfer, where they apply what they’ve learned in real-world settings; and impact, where these applications lead to broader, long-term societal or organizational change. By aligning this model with a classic logic model common to non-profits (and the foundations funding them), educators can create a clear, compelling story about how their learning events lead to both immediate and lasting change in language familiar to funders.

Let’s look at four key ways the LTI model maps onto the non-profit logic model and how educators can collect evidence at each step.

1: Curricula and Workshops as Outputs

In a typical logic model, outputs are the tangible products that result from an organization’s activities. For non-profit education programs, outputs are the curricula, learning designs, and the workshops themselves — anything an educator creates with grant funds. For example, if a non-profit uses a grant to develop a training program on sustainable urban farming, the multi-week, activity-by-activity curriculum and the actual sessions delivered are considered outputs. These are the direct products that show what the investment has generated.

Collecting evidence of outputs is pretty straightforward. Educators can document materials like participant guides, syllabi, or handouts. Keeping track of attendance records helps demonstrate how many people took part. And feedback forms from participants after the event can be an easy way to show that the workshop happened as planned and that participants were engaged.

2: Learning as an Outcome

In the LTI model, learning refers to what happens during the event itself — the “a-ha” moments when participants start grappling with new ideas or skills. In a logic model, this aligns with outcomes, the changes in knowledge, behavior, or perspectives that result from those outputs. Imagine a leadership workshop where participants actively work through collaborative decision-making strategies together. Their learning — demonstrated by how they apply the concepts in real-time during activities — is the key outcome of that event.

Capturing evidence of learning can take various forms. Educators can gather tangible products like project plans, group presentations, or recorded role-plays participants create together during a course. They can also use rubrics to evaluate how deeply participants grasped the new concepts or demonstrated proficiency in new skills. This kind of real-time evidence helps funders see that learning isn’t just theoretical; it’s happening during the event and giving participants the tools they need to take those new skills into the real world.

3: Transfer as Short-Term Impact

After participants leave the workshop, we move into the transfer phase of the LTI model, which corresponds to short-term impact in a logic model. This is when participants begin applying what they’ve learned in their everyday lives. Think of a participant who attended a conflict resolution workshop and starts using new mediation techniques to handle disputes at work. This phase is critical because it shows that learning isn’t confined to the workshop — it’s being transferred into real-world settings.

To collect evidence of transfer, educators can follow up with participants through surveys or interviews a few weeks or months after the event. They can ask for specific examples of how participants have put their new skills to work or request progress reports that show practical application in their communities or organizations. Making these surveys tied to specific actions demonstrated during the workshop can help respondents make quick before-and-after connections and respond promptly.

4: Impact as Long-Term Change

The final stage of the LTI model is impact, which maps onto long-term impact in a logic model. This is where the ripple effects of learning are felt more broadly. For example, if participants from an environmental sustainability workshop go on to start urban gardening projects or advocate for green-friendly policy changes, that’s the long-term impact of the learning they received. It’s the kind of change funders are most eager to see–but often the hardest to measure.

Collecting evidence of long-term impact requires more time and effort. Educators might consider conducting case studies of participants who have made significant changes in their fields or gathering community feedback on initiatives launched by alumni of the workshops. Testimonies, longitudinal studies, or formal evaluations of policy changes can provide the evidence needed to demonstrate that the learning has resulted in systemic, lasting change.

However, in cases where educators don’t have the funds to conduct extensive longitudinal research, they can still make a strong case to funders that the tangible evidence of Learning and Transfer they’ve collected makes a solid case that long-term Impact will follow. By clearly demonstrating that participants have integrated new knowledge and are already applying it in their communities or workplaces, educators can build a logical argument that these early changes are leading indicators of future impact. Funders understand that immediate outcomes and short-term impacts often lay the groundwork for longer-term systemic change, and presenting this logical progression can help strengthen their case for continued support.

By connecting the LTI model to the classic non-profit logic model, educators can give funders a clear and compelling picture of how their investments lead to meaningful, real-world change. From outputs like carefully crafted curricula to the long-term impacts of systemic change, this framework helps educators track, measure, and communicate results. Not only does it show the immediate benefits of learning, but it also demonstrates how that learning can lead to real behavior change and long-term transformation, making a strong case for continued investment in educational programs.

© 2024 Philip Silva